Amandla Ooko-Ombaka is the 2015 Harvard Business School Recipient. She used her grant from the Foundation to work on a book about her father, Oki Ooko-Ombaka. Read on to learn more about Amandla’s project.

Amandla Ooko-Ombaka is the 2015 Harvard Business School Recipient. She used her grant from the Foundation to work on a book about her father, Oki Ooko-Ombaka. Read on to learn more about Amandla’s project.

Our Unfinished Work: The Biography of Oki Ooko-Ombaka

What the life of a young Kenyan with an extraordinary commitment to making a difference in the world can tell us about our past, as we seek lessons for the future

Synopsis of the Book Project

Fifty years after many countries on the African continent fought for independence, we stand at a crossroads. Young Africans are leading the ‘second wave’ of independence movements across the continent from South Africa to Egypt. We are demanding systems of governance that work for us, and rejecting leaders whose autocratic styles and cults of personality remind of those who dominated our political landscapes in the past four decades. The hope and expectation for change is so ripe, we can taste it.

However, even as we reject some elements of the past, we need to intimately understand it if we are to move forward with purpose and direction. The story of one Kenyan, Oki Ooko-Ombaka has inspired, and continues to inspire a nation. He was born on the side of the road in a rural Kenyan village and worked his way to Harvard Law School. Oki died 3 months shy of his 50th birthday as one of the lead architects and authors of the Kenyan constitution after a long career in politics and public service. Our Unfinished Work: The Biography of Oki Ooko-Ombaka uses his life as a lens to intimately understand who we are as young Africans, how we find ourselves at the cross roads that will define our next 50 years. It is a call to action to pick up where Oki left off, and build an Africa we can all be proud to call home.

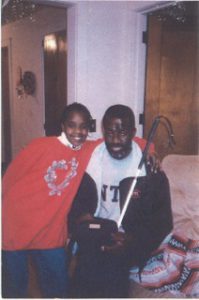

Oki was my father. He passed away in 2002 when I was 13 years old after almost a decade of battling cancer that rendered him blind. We lost our mother soon after in 2005. Since then, my two younger siblings and I have been trying to navigate the legacy our parents left behind, and our place in it.

Why Write?

This book project started as a personal catharsis. More than a decade ago, my late mother would muse that we should write a book about Oki. While my father was a hero to many, to my younger siblings and me, he was just our father. The father we would jump on for hugs as he walked through the door just in time for dinner. The father who amazed us with his wizardry when he solved our seemingly impossible math homework. The father who taught us about current affairs by making us read the newspaper to him on the long weekend drives to his rural home in Western Kenya when he was campaigning to be a Member of Parliament.

When he passed away 14 years ago, I felt like I had to preserve my memories of him as they were. I had to hold them still in the depths of my brain so I wouldn’t lose them, so I could keep them pristine for my younger siblings who were only 9 and 11 when he died. I had to protect them (the memories, but also and my siblings – a story for another day…) so they would not be tainted by anyone or anything. My father was perfect to me. For almost a year after he passed away, I would go into his room every day at 7pm, hoping, willing and praying for him to be there. That God would say just kidding, the past year was simply a bad dream.

As much as protecting our childhood memories of our father helped us grieve – especially as the visits from his ‘people’ became less frequent – it repressed our ability to have a richer and more complex appreciation of him. Now, as my siblings and I (‘the Okilets’) continue to try this thing called figuring out life, we are yearning for our memories of him to be fuller, more dynamic. To hear his advice on that next job – which is better aligned with our purpose? To hear his musings on our aspirations to serve in public office – are we really cut out for it? To cry on his shoulder about the significant other we just broke up with – was it worth it?

So I am embarking on this book project to try and understand the full man that my 13 year old self could not – the jurist dedicated to human rights. The instigator who built community with ‘troublemakers’ who have changed the world – amongst them the late Nobel Peace Laureate Wangari Maathai (dad was Maathai’s lawyer in landmark case against the Kenyan government that catalyzed the Greenbelt movement). The persistent servant leader whose life was threatened for serving and protecting those unable to defend themselves. The sterling academic and voracious reader who had to battle with losing his sight at the prime of his career. The ‘most eligible bachelor in Nairobi’, and stories from his countless admirers. The husband to my phenomenal woman of mother, who would constantly remind him that she was the only real Doctor in the house.

Why now?

In as much as this book is a personal catharsis, the more I work on it, the more it grows into a broader call to action for young Africans like my siblings and I.

Countries across the continent are experiencing the real rumbles of ideology based political movements. These rumbles are the guts of what Oki stood for, a political dispensation distinct from ‘cult of personality’ politics that still characterize so many of our political landscapes today, more than 50 years after independence. The urgency of telling Oki’s story as a call to action has only increased given my recent post-graduation move back home to Kenya after 12 years living, studying and working abroad. My political identity is inextricably linked to his.

We see these rumblings in the Arab Spring pushing for democracy and equal representation. We see them in the political elites facing the justice system for corruption charges in East Africa. We see them in the rise and reform of Julius Malema in South Africa. In the context of these changes, my generation must be deliberate with the legacy we want to build for the continent. The energy for change across the continent is infectious and intoxicating. But we cannot keep voting out and/or overthrowing leaders, and then asking “now what”, or wondering why the progress we were pushing so hard to achieve has not happened. In order to be deliberate with where we are going, we need to understand where we have come from – in our words, with our stories.

I so firmly believe that Oki’s story is a lens to explore many of the big questions of political identity that my generation of Africans is grappling with. The decisions Oki made over the course of his life track Kenya’s young history as a democracy; he was as born at a time when Africa was fighting for our independence from colonial powers. He was a university student leader in the mid-70s when his passion for multipartism led to his torture and exile from Kenya. He was a member of parliament at the height of Africa’s “lost decade”. He left politics to dedicate his life to writing Kenya’s new constitution – arguably the most important political legacy of his generation. If we replace colonial powers with the post-colonial old-boys network (i.e. Presidents and families who have been in power for decades), multipartism with ideology based politics, and lost decade with Africa Rising rhetoric, we are operating from the same playbook as Oki. He had to ask himself then many of the questions we are asking ourselves now, more than 50 years after independence – who we are as young Africans today, and what role do we want to plan in shaping the trajectory of the continent for the next 50 years?

How far along am I?

When I share with people that I am writing a book, the first question they often ask is how far along am I? I have decided that this is the writer’s equivalent of “When are you getting married?” to any woman above 22, or “When are you having kids?” to any newly married couple. The short answer is that I have a book prospectus, 9 chapter outlines, one good full chapter, two less good full chapters. The longer and more real answer is that somedays I feel like I could get a first draft of the book ready in a matter of months. Other times, I am so overwhelmed with this project, that I question why I started it in the first place. But I remain grateful for the Fitzie Foundation Fellowship that has allowed me to take the real time I need to catalyze this decade old passion project.

I have started a Word Press to document the writing process (here), as well as solicit stories and advice from the universe writ large. Most of the entries right now are private – I thought I was ready to publicly share many of these thoughts and feelings I am experiencing. It turns out I am not. In the midst of this writing process I am uncovering memories I didn’t know I had repressed, and I’m tapping into wells of emotions so deep I sometimes feel like I’m drowning in them.

So I’ve decided instead share a short story a week that has moved me about my dad until I am ready to share more publicly the ups and downs of the writing process. The first anecdote is online here. And I also keep a running HELP & SUPPORT ME section on the website with asks of the universe (if you proclaim it, it must come true yes?). Right now, my priority is finding an agent. If you have any leads, hit me up at aooko.ombaka@gmail.com.

Until next time,

Onwards!